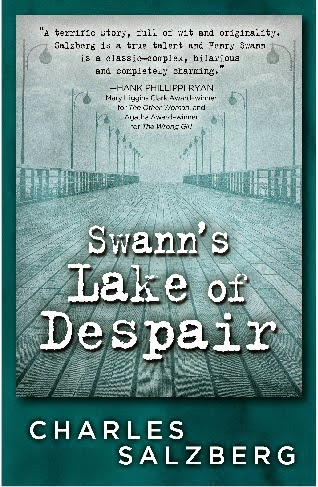

Fans of Charles Salzberg's Henry Swann will be pleased to know that the third in the series comes out a week from tomorrow. A New York-based novelist, journalist and acclaimed writing instructor, Charles is the author of Devil in the Hole, chosen as one of the Best True Crime Novels of the Year by Suspense Magazine, and the Henry Swann detective series featuring Swann’s Last Song, which was nominated for a Shamus Award for Best First PI Novel; Swann Dives In; and the upcoming Swann’s Lake of Despair.

I never planned on being a crime writer. And yet it probably turned out to be the best thing possible for my writing career, which began for me, as it did for so many other English majors, with a desire to write the Great American Novel. But I was self-aware enough to know I’d never write a great novel, one that came even close to my heroes, Nabokov, Bellow, Roth and Mailer. Instead, I was willing to settle for a good literary novel.

But when I realized that wouldn’t pay the rent I stumbled into a career as a magazine journalist. Although I wrote about pretty much any subject under the sun, I was always fascinated by crime and even worked on a true crime book called Dead End. But I never stopped writing fiction and about 25 years ago what started out as an experiment in writing what a friend of mine called, “an anti-detective novel” ended up as a novel called Swann’s Last Song. The novel begins with a murder having already taken place and there are several other random unconnected killings along the way, but it’s really about identity since Swann, who abhors violence and whose specialty is finding lost people, winds up not trying to find the murderer but rather to find out who the victim really was and, along the way, who he is. I, of course, thought it was a brilliant idea, but agents and publishers didn’t share my enthusiasm. And so, for twenty years the novel languished on my computer, until I dusted it off, updated it, and finally “sold out” by having Swann solve the crime. Boom! It sold. (You can actually find my original ending in the paperback edition.)

Although written as a one-off (in the original version Swann becomes so disillusioned he quits the business), to my surprise it was nominated for a Shamus award and when I lost I got pissed off enough to decide I’d keep writing them until I won something.

With no offense to my fellow crime and mystery writers, because I admire so many of them, I decided to take a different path within the genre. Each Swann novel was going to present me with a different challenge. To me writing the traditional detective mystery, where there is a dead body, a host of likely suspects, the detective solves the crime and the book ends, was a kind of death in itself. The truth is, I couldn’t do that even if I wanted to, because I’m not particularly good at tight plotting nor with lining the pages with clever clues for the detective and reader to follow.

Instead, I decided to not only focus on character but also push the envelope in terms of what people might expect in a detective novel.

For instance, in the second in the series, Swann Dives In, not only are there no dead bodies but the reader isn’t quite sure what the crime is until more than half-way through the book and by the end of the book isn’t even sure a crime was committed.

In the third in the series, Swann’s Lake of Despair, I set myself another challenge. I would have Swann investigate three separate cases at the same time, each unrelated to the other, none of them involving murder.

Why? Because to me murder is overrated. On TV each week the viewer is assaulted with perhaps twenty to thirty murders—and in a show like The Following, there can be that many murders in a single episode. But in real life, how many of us are actually affected by murder? Sure, we read about them in the newspapers and hear about them on the television news, but for the most part, it’s not our reality. On the other hand most of experience or even commit other kinds of crimes every day, sometimes more than one. They might be petty crimes, like stealing supplies from where you work. Breaking a loved one’s heart. Cheating on a test. Lying. Misrepresentation. These crimes might not be punishable by a stint in prison, but they are crimes nonetheless. And they can be very personal crimes: crimes that might hurt us deeply.

These are the kinds of crimes I’m more interested in writing about and these are the crimes Swann is called on to solve.

Thinking back, I realize I was profoundly influenced by a 1960s television series called The Naked City. What would be called a police procedural today, there was, of course, a crime committed every week. But often these crimes did not involve murder. Instead, the show, which had “eight million” stories from which to draw, focused on character, deceit, unhappiness; on broken hearts as much as broken heads.

This is what I tried to capture in Swann’s Lake of Despair. In one case Swann is hired by a distraught fellow whose girlfriend has disappeared. His heart is broken, he feels betrayed. In another, Swann seeks to find a lost journal that might shed light on an eighty-year old death that might or might not have been murder or suicide. In the third, he’s hired to find a portfolio of lost photographs by a long since deceased photojournalist. The latter was inspired by a friend and former student of mine, Julia Scully, a wonderful writer whose second memoir in progress (her first was called Outside Passage and was published to wide acclaim), told about her life as an editor in the world of photography in the 1950s and ‘60s. Julia allowed me to ransack her life for this plotline.

And so, if you’re looking for dead bodies, you probably won’t find them in my Swann books. But then again, I love to break rules, even my own, and if it just “happens” organically in the plot, well, you never know, blood might just flow someday.

© 2014 Charles Salzberg

I can't wait to read your books! Thelma Straw in Manhattan

ReplyDeleteThanks, Thelma.

Delete